At University of Alaska Anchorage, two students are on an interdisciplinary quest to unlock the anthropological and archaeological importance of caribou teeth.

Yes, caribou teeth.

Anthropology student Nathan Harmston is merging ancient migrations with modern science in his graduate research project. Much like annual tree rings, he said, caribou teeth add a layer each day, acting like a biologic calendar during the tooth’s growth. These layers absorb nitrogen, carbon and strontium isotopes from the environment, showing not just where an animal grazed, but when. Analyzing these stable isotopes in growth lines can turn a tooth into a tracking collar from the past, opening up a world of lost information.

“It’s a map of your food sources,” said UAA chemistry professor Patrick Tomco, who advises the chemistry side of Harmston’s interdisciplinary research. The complex project — which blends chemistry and archaeology to answer questions of anthropology — seeks to fill in the history of Alaska’s caribou migration.

For his research, Harmston plans to identify whether today’s caribou herds are different from those in the past. If entire herds have died out, then dependent human communities may have likewise vanished, leaving traceable but undiscovered archaeological sites across large swaths of Alaska.

“There’s potentially an important part of the Native cultural history that’s being missed and overlooked,” Harmston said, noting that models for locating archeological sites generally focus on known migration routes, where herds and humans interact. Separate extinct herds, he said, would “allow archeologists to reevaluate our model of human use” of the landscape.

The truth is in the tooth

To find extinct caribou herds, though, Harmston needs those chemical tracking collars in the teeth. One major problem: teeth grow brittle and crumbly when buried, making the cross-sectioning process all but impossible. Alaska agencies aren’t likely to hand over centuries-old specimens until Harmston can find a way to stabilize teeth, and prove his process works.

By turning to UAA’s chemistry department, Harmston found not just a solution to his problem, but cross-campus collaborators as well. He’d read about the stabilizing potential of polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), also known as Plexiglas, which was available in UAA’s chemistry storeroom. Tomco — who’d purchased the acrylic polymer for an organic chemistry lab — got in touch with Harmston, and their quick talk turned into a deeper dialogue. Tomco soon offered research space in his lab, as well as a student assistant in Erik Linduska.

Harmston was happy to have interdisciplinary help. He would bring the ethnographic research if Linduska, a natural sciences major, would help permeate trial teeth with polymers, then powderize and prepare milligrams of dental tissues for isotopic analysis. Conveniently, Linduska had worked six years as a dental health provider in the Aleutians. Undergraduate research — on teeth, no less — could only help his dental school applications.

“It was just this really interesting collection of people with their own interests,” Tomco said of the “Alaska-specific” collaboration. UAF’s Large Animal Research Station and the Alaska Department of Fish & Game donated recent teeth to work with. Even the engineering department got involved, providing access to equipment, tools and lab space. “All of this is done at UAA. All of it,” he added.

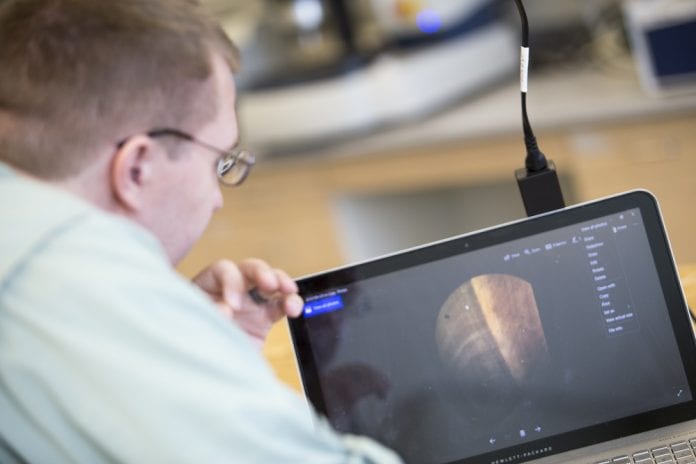

To extract individual tooth layers, Harmston and Linduska encased modern caribou teeth in PMMA. Their method mirrors how dentists apply crowns — embedding liquid into a tooth, then solidifying it with heat. However, while dentists match the crown to the bite, Harmston and Linduska just needed stability. Their finished product looks like a tooth encased in a Plexiglas hockey puck.

The current research is still heavy on chemistry, as Harmston and Linduska test whether the carbon-based PMMA polymer can be used without contaminating the tooth’s natural carbon isotopes. So far, it’s good news. After analyzing wild specimens from Fish & Game versus the controlled-diet caribou from UAF, Harmston and Linduska identified all caribou teeth incorporate the same ratio of carbon from PMMA.

“Caribou from drastically different herds are incorporating the polymer consistently,” Tomco explained. “They both incorporate the same amount, which tells us this method can be used.”

Past migrations, modern implications

On the surface, it’s odd research for an anthropologist. But the addition of chemistry, biology, engineering and a bit of dentistry has made the research stronger.

“You’re getting drawn in from all these other resources, which is amazing,” Linduska said of the research. “It’s a great way to look at something in a ton of different ways.”

“It really broadens [what] can be answered,” said Harmston, who specifically studies zooarchaeology, or the interaction between animals and human behavior in the

archeological record. “We’ve largely been asking the same questions of animal remains for the past 200 years. What animals were present? What were people eating? How did they butcher it?” Adding chemistry to the conversation brings a whole new line of possibilities.

Fitting of his project’s breadth, its implications are similarly diverse, and federal land management agencies are already taking interest, he said. Knowing the locations of pre-contact and early historic herds could fill in missing pieces of Alaska Native history. Likewise, identifying possible archaeological sites could affect land use and permitting on federal lands. Importantly, knowing where animals thrived in the past is the first step in addressing why they died out. The information could explain how herds respond to the extinction of other herds, and guide any reintroduction efforts of caribou across the state. So add one more academic discipline to the project: conservation biology.

Though his project explores the past, its modern practicality is especially important to Harmston.

“Archaeology has a long history of being a luxury science, answering questions of interest but not questions of practicality,” he noted. “I’m really interested in making archeology, and zooarchaeology in particular, applicable to real world problems.”

J. Besl highlights alumni stories and campus events at UAA.