The first hatchery in the Cordova area was located a mere seven miles from town, on what is now known as Power Creek Road.

Today only a wide turnout, plus two large culverts that are a popular viewing area for spawning sockeye, and also brown bear looking for a tasty treat, give hints of its past. Remnants of a wooden bridge that led to the hatchery that was situated above the parking area can be seen if the water level is low.

A fascinating chronology of events leading to the establishment of this hatchery can be found in paper titled “History of Eyak Lake” by the Copper River Watershed Project.

In 1871, just six years after the end of the Civil War and four years after the purchase of Alaska from Russia, the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries was established “to determine the cause of decreasing salmon runs.”

In 1889, those concerns resulted in the establishment of the first Alaskan hatchery in Kodiak and made it unlawful to build obstructions to bodies of water offering habitat for salmon. By the late 1890s, government hatcheries had been abandoned; and canneries, wanting to protect their own interests, created their own.

In 1900, the government made it “mandatory for any person, company, or corporation taking salmon in Alaska waters to produce sockeye fry in at least four times the number of mature salmon taken.” The ratio was increased to 10:1 in 1902. After many failed operations, the mandatory hatchery law was replaced by a rebate system of 40 cents for every 1,000 fry released.

In 1917, the Territorial Fish Commission set aside $80,000 to build two new hatcheries, one in Seward, the other near Eyak Lake.

The Watershed Project paper details the ensuing events at Power Creek in marvelous detail.

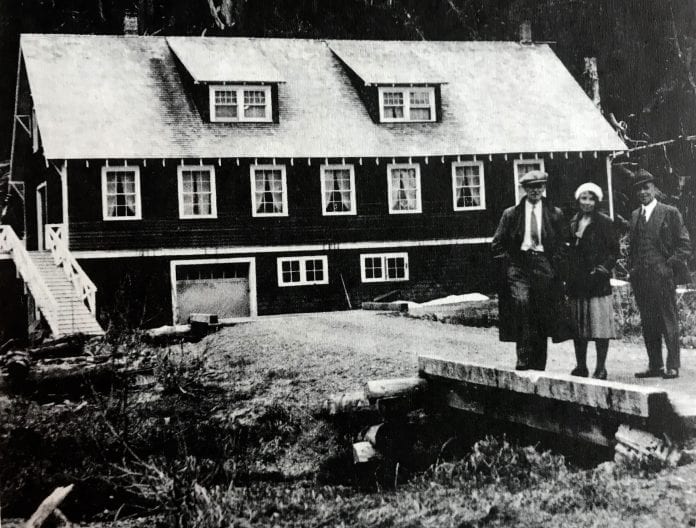

“In June 1921, Al Sprague guided construction of not only a new hatchery, but also roads, rails, bunkhouses, outdoor troughs, and a 1,400-foot pipeline to create a salmon pond. The first year, 12 million Chinook eggs were taken, but because the egg baskets had not arrived, once the eggs were eyed, half of the eggs were buried into Power Creek and half into Spring Creek.”

Sprague didn’t last long. He was fired in December 1921 for “frivolous spending on the hatchery.” Edwin Wentworth took over the operation in 1922, planting 3 million sockeye eyed eggs.

“In 1923, a new hatchery building was erected, and methods became more sophisticated. Now able to rear fry, Wentworth released 3.8 million sockeye fry by Jan. 24, 1924. The hatchery attempted to lengthen the rearing process in its 1924 egg take, however, a flood in August 1924 liberated the 3.2 million fry.”

Hmmm. It would seem the recent issues with flooding damage to the road that have impacted buried power lines from the Cordova Electric Coop Power Creek hydro project a mile above the old hatchery site are nothing new.

The report continues: “In the egg take of 1925, 7.3 million fry were released by early November 1925. Funds had run out; with high expenses for heating, lighting, payroll, and running a predator control weir that destroyed any cutthroat trout or Dolly Varden from entering the lake. By 1926, the bunkhouse had burned and by 1927, the U.S. Forest Service took ownership of the hatchery. The old hatchery building became the Bethany Home for Children in 1938.”

Today, the ADF&G estimates that 20,000 sockeye spawn annually in Eyak Lake, supporting a late run of reds that local fisherman can differentiate from Copper River reds by their color and shape.

The average estimated number of sockeye spawning in the Power Creek area over the past four years is 2,200. Multiply that by the average number of eggs per sockeye, which is 3,500, and the result is over 7 million eggs.

That total is interesting to compare with egg and fry counts from the brief hatchery operation there, which included 3 million eggs in 1922, a fry release of 3.2 million in 1924 and 7.3 million fry in November, 1925, before the operation was shut down.

Current local ADF&G biologists were skeptical about the success of that last release in 1925, as it was even before hard winter had likely arrived.

And of course, even today, fisheries biologists candidly admit no one knows for sure what happens to all those fish once they head out into the far Pacific.

It all comes down to the luck of the draw for tiny pink spheres that are amazingly similar in color to the big plastic buoys that fishermen drop off the bows of their boats come the start of another fishing season.

And it appears the odds were not “eggs-actually” too good at Cordova’s first hatchery back in the early 1920s.