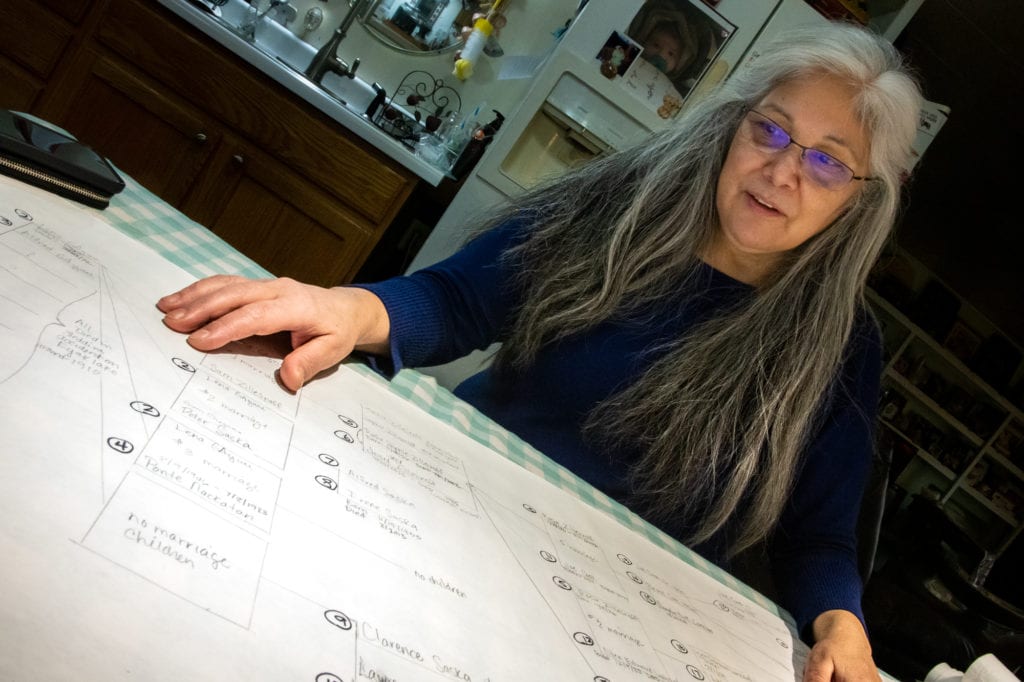

Over the last three years, I have watched my mom, Pam Smith, work on an immense genealogical research project. She has spent hours poring over newspaper clippings, old census documents, and her own interview notes in order to reach her goal: to document every single Eyak person. She sketches out her genealogies in pencil, writing on white butcher paper otherwise reserved for wrapping up deer and moose meat for the freezer. She stores the many rolls of genealogies in a Coca-Cola cardboard box, which make her years of work appear far less monumental than they actually are. She has created the most in-depth genealogical research for the Eyak people to date by documenting the genealogical lines of over 10 Eyak families, including ours. Her research shows that today there are more than 400 living Eyak descendants, information gleaned from dozens of interviews with Eyak people across Cordova, Glennallen, Anchorage, Valdez and Yakutat.

When I asked her why she decided to undergo such a massive project, she replied that she always had an interest in genealogy, but that the main reason was because of a conflict over the use of a burial ground at the Eyak Lake spit.

“When you and I decided to stand up for the spit area, it became really heated,” she said. “One day I was on Main Street and a community member walked up to me and said, ‘So who are the Eyaks anyway? Are there even any Eyak people left?’ I was so stunned that I said ‘There sure are! I am one!’ So that comment really got me started.”

The general notion that “there are no Indigenous people left” is a common misconception. It’s not a surprise that this kind of thinking also permeates small-town life and would be asked about Eyak people. It doesn’t help matters that Eyaks have always been on the smaller side in numbers, anthropological and ethnological literature written about us is quite thin, and that Eyaks are the only Native group in Alaska to have our language temporarily fall asleep.

Many historical records have miscategorized us, often confusing us with our Native neighbors of the Chugach area, not understanding that Eyaks are a distinct people all our own. This genealogy project of this magnitude, in part, helps rectify some of these longstanding historical inaccuracies and modern misconceptions about who and how many the Eyak people are.

“I began with our family,” she told me, when I asked her what her process was. “I went to my brother Joe Cook as the eldest of the family and he wrote out the beginning of our family tree. I took that document to the rest of my siblings and we kept adding. Then, I documented my Aunty Irene Hansen’s family in the same way.”

By virtue of local knowledge accumulated over the years of having lived in Cordova all of her life, she already knew many of the Eyak families.

“When I was young my grandma Lena would take me to Old Town to go visit her friends like Jenny James, Barbara Olsen, Exenia Barnes and Sophie Borodkin. She always made it clear to me who was who, and which ones were Eyak. Also, throughout my life I would hear stories and rumors about up-river Eyaks in Chitna and many Eyak families in Yakutat.” Through her interviews she also heard stories about other individuals and families who had connections to Eyak, and so the project continued to grow.

Many of her winter afternoons have been spent sitting with elders of Eyak families for hours at a time over lots of tea and coffee.

“I spent probably 20 hours with Ginger Clock,” Smith said. “She’s amazing. She has a library that goes back 200 years. I also relied heavily on Anna Nelson Harry’s family to put me in touch with her descendants. I sure wish Elaine Abraham was still alive. If she were, I would sit in her living room and ask her questions until she threw me out. I also spent a lot of time with Ira Grindle. I use him like an encyclopedia with all of the research that he has done. I would take him a name and he would give me all of the research and photographs that he had that was relevant to that name. Many of the people I interviewed also shared their family photographs with me, so now there is quite the collection of names and images.”

While many people were very open to sharing their family histories, not every door was always open.

“Sometimes I was limited by people who didn’t want to share,” she said. “There are a lot of stories and things that are hard and heavy duty for people to talk about, and I try to be sensitive to what people are willing to share or not. Not every story is a happy one.”

Yet, the genealogy project has been overwhelmingly received as important work.

“One elder, Ray Craig, burst into tears when I told him what I was doing. He was so grateful because no one had taken the time to be specific about who the Eyaks are, and he had waited all these years to feel a kinship with his people.”

As meaningful as the work has been to elders, she also enjoys the potential it has for Eyak youth.

“I like seeing these young Eyaks around town and I ask them, ‘do you know how you’re Eyak?’ When they say ‘no,’ I show them their genealogy so that they can learn.”

She also shares her work at Eyak culture camps held each the summer.

“I rolled out all of my genealogies to show everyone how many of us there are,” Smith said. “I brought sticky notes for people to add stories and names that I had missed.”

This addition to the camp every year has offered a new dimension of reconnection. Barbara Pajak-Sappah reflects on the genealogical project by saying, “at one point, people were saying Eyak was dead. This shows, we are alive, and there are plenty of us. Our families are able to connect and share our experiences. It’s helped give us life, no matter what others say.”

The genealogy project has acted as a catalyst for bringing the Eyak community together, as many of us are splintered out across geography and organizations as shareholders and/or tribal members. For Eyaks, there isn’t just one organization that brings all of us together under one umbrella. The genealogy project is one way to remedy that.

This work “sparks and ignites something in each individual I’ve talked to,” My mom told me. “Many believe that they are being acknowledged for maybe the first time in their lives that they are Eyak and that they are connected to their land, language and history. This project is way bigger than me; I’m just writing names down on paper. But in doing so, I’m happy that this work can make Eyak people feel like they belong.”

The work is far from finished, but the project is already significant and unprecedented. In the near future, there are plans being made to travel to Yakutat to bring together Eyak people from Cordova and Yakutat, another way to enrich the Eyak community.

Smith ended our interview by saying, “This project hasn’t been funded by anything but the energy that comes from me. This is an intentional choice so that this information belongs completely and solely to the Eyak people.”

For those who would like to share their Eyak lineage with Pam Smith email her at eyakgenealogyproject@gmail.com.