Prince William Sound Science Center research assistant Anne Schaefer is headed south for her second year working with penguins for long-term seabird research projects in Antarctica. This year, in addition to six weeks of at-sea seabird surveys aboard a research vessel, she will be spending a month doing land-based field work at Palmer Station, Antarctica.

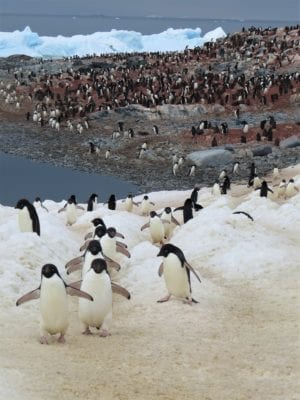

Palmer Station is on an island surrounded by several other small islands where colonies of seabirds including three penguin species (Adélie, chinstrap and gentoo), giant petrels, and skuas nest. The research team Schaefer will join will be out in the field for long hours every opportunity that weather and ice conditions allow. When they do go to the islands Anne expects to work long hours, not unlike the week she spent collecting data on Avian Island in Antarctica last year. Some days, Schaefer said, they would start in the morning and not get done until 11 p.m. or midnight. However, while they are based at Palmer, they have to be back on station by 10 p.m.

Schaefer is especially excited about this portion of the trip because she will have the opportunity to do more hands-on work with penguins, such as collecting body measurements and deploying tracking tags. The type of work is similar to what she does at PWSSC in Cordova with tufted puffins, gulls and shorebirds.

She will be taking the same types of measurements: flippers (wings), bill length and body weights. She will even use the same tools, but the technique is different.

“You handle penguins way differently than you do other birds.” Schaefer sayd. “They are tough, strong, heavy creatures.”

The data they are collecting is for a variety of different long-term monitoring studies led by William R. Fraser of the Polar Oceans Research Group. The studies vary by species, but they’re all related to abundance, reproduction and foraging behaviors of seabirds as the climate shifts in Antarctica.

After a month at Palmer Station, Schaefer will work aboard the 230-foot icebreaker research vessel Laurence M. Gould for four weeks. Her job on the boat is to alternate with one other person to identify and count every bird she sees on survey transects during daylight hours. This is also similar to the work Schaefer has been doing here at the science center for the last few years with the Fall and Winter Seabird Abundance Monitoring project. This time though, instead of common loons, red-breasted mergansers and buffleheads she will be seeing albatross, giant petrels and more penguins.

The research cruise follows a very specific grid along the coast of Antarctica known as the Palmer Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) survey site. It is part of the National Science Foundation’s network of 28 LTER sites around the world — including one in the Northern Gulf of Alaska. Each site measures the same site-specific parameters in the same timeframe year after year to provide a long-term public data set. The Palmer LTER site’s survey grid is surveyed every year in January by a variety of researchers studying every level of the ecosystem.

The seabird component is an important part of this whole ecosystem approach because studying marine birds can tell us what is happening under the surface based on where they are distributed and how abundant they are. A seabird survey like the Palmer LTER with a set grid and time frame can give clues into what’s going on with a whole ecosystem as things change over time.