When you put your thumb over the end of a garden hose, the water squirts out twice as hard. Something similar is happening along the Copper River Highway, where narrow, collapsing and clogged-up culverts have produced currents too strong for salmon to swim against. These culverts have, in effect, cut fish off from dozens of miles of upstream habitat.

Many of these roughly 3-foot-wide culverts were installed around World War II, using whatever supplies were available. Some were installed improperly, while others have simply been unable to keep up with increased glacial melt.

“Sometimes we don’t even know who put it in,” said Megan Marie, habitat biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “It might have been put in by a landowner a long time ago, or it might have been put in on state land illegally.”

Running east-to-west, the Copper River Highway is crossed by many streams running north-to-south. This required the building of as many as 50 culverts along a single 15-mile stretch of highway. At the time, engineers designed culverts simply to get water from A to B, said Heather Hanson, fish passage engineer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The broader effects of these culverts usually weren’t taken into consideration.

“If you’re a highway engineer, your object is to get the water from one side of the road to the other as efficiently as possible and with as little cost as possible,” said Forest Service hydrologist Luca Adelfio. “So, you put in a smaller, steeper culvert so the water flows through faster. But that’s problematic if you’re a small fish.”

In some areas, narrow culverts gushing with high-pressure current have become a dead end for spawning salmon, who end up stuck at the mouth of the culvert. The only winners in this arrangement are seals. Kate Morse, program director for the Copper River Watershed Project, recalls watching seals line downstream of a culvert to dine on a buffet of salmon.

However, it’s juvenile salmon that are most affected when a 15-foot-wide stream is pushed through a 3-foot-wide culvert. Small tributaries, often no deeper than the top of an Xtratuf boot, are vital to the maturation of young salmon. When relatively small and weak juvenile salmon can’t swim through a too-full culvert, any habitat upstream of that culvert has been locked away from them. In some areas, high-velocity flows have altered the streambed near the downstream end of the culvert. As a result, during dry weather, the mouth of the culvert may become “perched” above the stream, accessible only to fish large and strong enough to jump up into it.

Beavers also seem to enjoy damming up these narrow pipes, Adelfio said. Drawn by the sound of trickling water, beavers jam the culverts full of debris until the Department of Transportation has to come by with an excavator and clear it out by pushing a large log through the culvert.

Even if the suffering of juvenile salmon doesn’t tug at your heartstrings, there’s still reason for concern. As summers heat up, water flow around the Copper River Delta is expected to increase, Morse said. Flow levels that would have been exceptionally high when the culverts were installed now occur multiple times per summer. When water exceeds a culvert’s capacity, it can wash across the surface of the highway, causing lasting damage.

“It’s a very dynamic [water] system that wants to move and change,” Morse said. “But there’s a static road and static pipes that it’s going to have to be forced through.”

Narrow culverts were chosen for the Copper River Highway, in part, to save money. The cost of upgrading them could rise to $750,000 per culvert. This may seem a steep price for something as mundane as a culvert. However, the alternative would require decades of applying on-the-spot fixes to failing pipes, said Darcy Saiget, acting Prince William Sound Zone Aquatics Program manager for the Forest Service. At one site, the culvert pipe itself was washed away in a flood event and carried downstream, making replacement inevitable.

“They can be really expensive to repeatedly fix, so it’s well worth the investment to replace them so that the infrastructure is protected,” Saiget said.

Drawing on information collected by the DOT and the Department of Fish and Game, the CRWP set out to identify the culverts most in need of removal or replacement, Morse said. This included not only the most decrepit culverts, but those connected to the most extensive fish habitat — in short, the worst culverts blocking the best streams. The CRWP also worked in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The CRWP picked out 13 “problem” culverts. Eleven would be replaced, one would be converted into a shallow ford and one would simply be removed, as the path it underlay was no longer used. For funding, the CRWP and its partners applied to the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council. Although EVOSTC would typically be expected to fund only one culvert replacement at a time, CRWP was able to make a strong case with the support of its partners, Morse said. The project received a single lump of funding to address the 13 culverts — a major boon to the project, Morse said. The projected cost of the replacements and removals ranges from $15,000 to $750,000 per culvert.

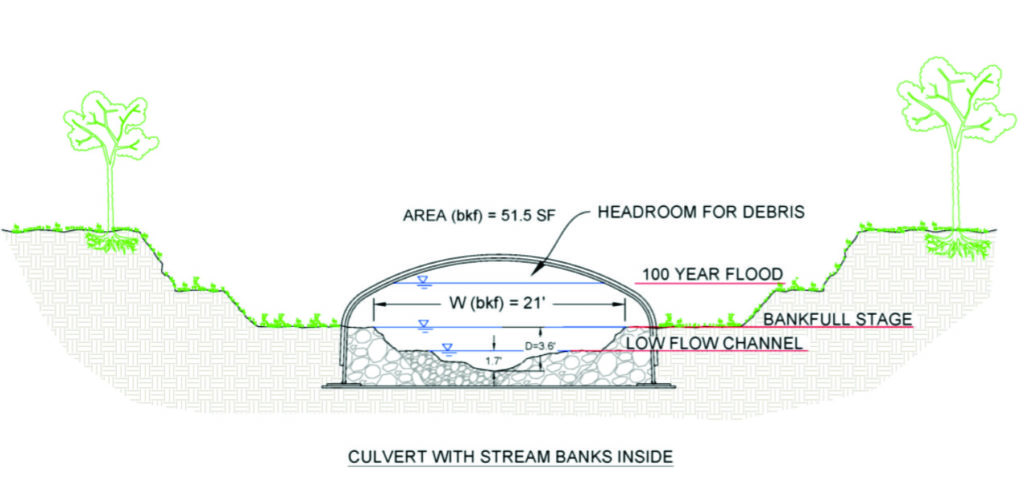

However, the 11 new culverts won’t simply be larger versions of the 3-foot-wide pipes currently deployed around the delta. The upgraded, roughly 16-foot-wide “box” culverts will leave a large gap above and around the stream, similar to a bridge underpass. This way, a natural streambed will be able to wind its way under the road, more or less undisturbed. Once put in place, the box culverts should last for at least a century, Morse said.

“The culverts we’re putting in mimic the stream channel,” Marie said. “They’re designed to simulate the natural stream conditions that you might see out there, and allow for additional functions like sediment transport and naturally moving high and low flows. They have actual banks… The bottom line, budget-wise, is that they perform well in flooding and don’t require the maintenance that the undersized pipes do.”

From a salmon’s perspective, swimming through a box culvert would be no different than swimming through a shaded stream, Saiget said. Replacing or removing these 13 culverts will unlock around 22 miles of upstream fish habitat, according to a Forest Service report.

The CRWP has previously been involved in installing sized-up culverts along the Copper River Highway. As well as allowing safer fish passage, they seem not to attract the attention of beavers, Adelfio said.

The 13 selected culverts will be removed or replaced over a period of five years, with the first three replacements occurring this summer. Work is planned to take place over either three separate 12-hour periods or one 36-hour period. Twelve-hour road closures would take place between 8 p.m.-8 a.m, Morse said.

“If these culverts are too small for flooding events, it’s going to close the road down anyway,” Morse said.

However, there will still remain dozens of too small, too steep or too dilapidated culverts placed around the Copper River Delta. Additionally, only culverts falling inside the area designated to have been affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill are eligible for EVOS funding. However, the Forest Service hopes to eventually replace all the undersized culverts on the delta, Adelfio said. In the years after the new culverts are installed, Cordova will see a return in the form of greater fish populations, Adelfio said.