Imagine a very large brick wall. Not all of its bricks are in great condition — some are weathered, others cracked and broken. But the wall stands, held together with generous quantities of mortar. Now, imagine you start removing the mortar from between the bricks. The wall remains stable at first, but, the more mortar you scrape away, the more likely it becomes that the entire structure will suddenly collapse on top of you.

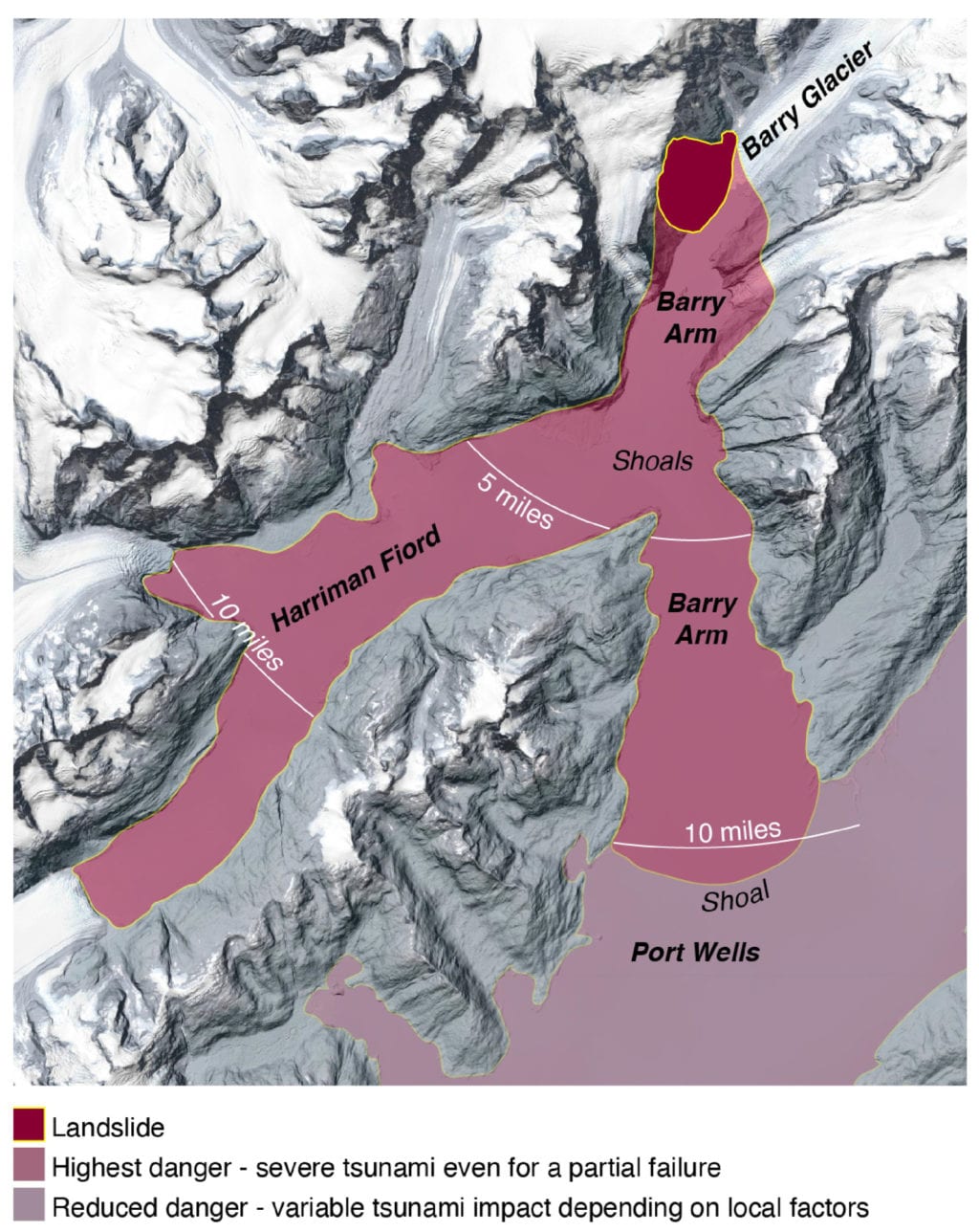

Something similar is occurring in northern Prince William Sound, where the rapid retreat of the Barry Glacier has destabilized part of the north wall of the Barry Arm fjord. If the affected area were to collapse all at once, it would be “like dropping about 500 Empire State Buildings into the ocean at one time,” threatening communities around the sound with severe tsunami damage, said Gabriel Wolken, a scientist specializing in unstable slopes.

A tsunami-causing landslide could possibly occur at Barry Arm within the next year, and will likely occur within 20 years, according to a May 14 open letter signed by 14 geologists and other scientists.

Many years ago, tectonic pressure forced sedimentary rocks to merge with the southern shore of the Alaska mainland, creating numerous cracks and weak spots in the terrain. Then glaciers spread across the landscape, causing further fracturing and erosion. Now, as glaciers and permafrost melt rapidly away, they remove support from geological structures, raising the chance of sudden collapses, according to a May 14 release from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys.

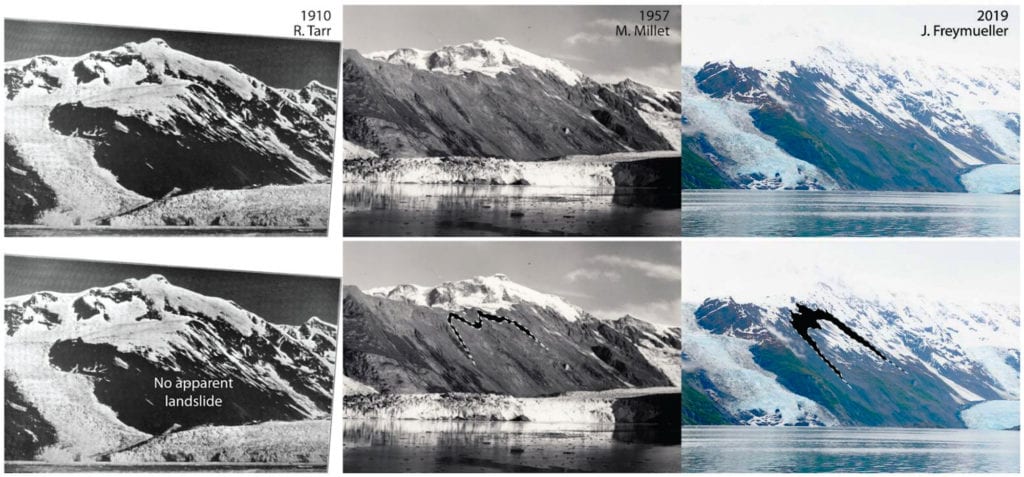

“You have a deterioration of the glue that, essentially, holds this together,” said Wolken, who manages DGGS’s Climate and Cryosphere Hazards Program. “Right now, what we do know is that this landslide and its motion are strongly correlated to the retreat of Barry Glacier… The landslide is more likely to fail and plunge into the ocean once that glacier moves out of the way.”

Barry Glacier has receded by a little over two miles since 2006 — a remarkably rapid retreat, Wolken said. If this process were to touch off a multi-million-ton avalanche at the Barry Arm, the resulting tsunami would be of historic proportions, said DGGS Director Steve Masterman. Though it’s impossible to predict when a landslide will occur, rain, snow and seismic activity could hasten its arrival, Masterman said.

“As global warming continues to thaw glaciers and permafrost, landslide-created tsunamis are emerging as a greater threat — not just in Alaska, but in places like British Columbia and Norway,” said Anna Liljedahl, a scientist at Woods Hole Research Center, one of the groups that helped first identify the hazard at Barry Arm around late April.

Wave would take 90 minutes to reach Cordova

Preliminary simulations, assuming that most of the landslide mass would fall at once, predict a tsunami spreading throughout the sound, impacting even bays and fjords far from the landslide site. Simulations performed by Patrick Lynett, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Southern California, projected that a tsunami would strike Whittier about 20 minutes after the landslide, reaching over 30 feet above the tide. Cordova would not feel the impact of the wave until 90 minutes after the landslide event. Though the wave would likely only raise the water by three feet, it could create dangerous currents around Cordova’s docks and harbor, pushing boats around. Cordova, Valdez and Tatitlek would be unlikely to experience onshore danger from the wave, according to simulations.

When facing a tsunami, moving to higher ground is usually more helpful than moving inland, Wolken said. At sea, it can be prudent to move to deeper water, where the wave may be experienced merely as a swell. It’s important that mariners around the sound keep their radios tuned to an emergency channel, he said.

The waters near Barry Arm attract many vessels engaged in commercial, sport and subsistence fishing, as well as recreational boaters and campers. During the summer, as many as 500 people may be in the area of Barry Arm and at risk from the potential landslide, according to a DGGS release. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game recommended that the public avoid the area. The U.S. Forest Service also strongly discouraged recreation at beach sites around Barry Arm and nearby Harriman Fjord in a Tuesday, May 19 announcement.

Landslides have set off giant waves elsewhere in Alaska during recent years. A 2015 landslide at Taan Fjord, west of Yakutat, triggered a 633-foot tsunami near the landslide site, causing 35-foot waves at a site 15 miles away, according to DGGS data. While the Taan Fjord landslide released about 80 million cubic yards of material, a landslide at Barry Arm could release up to 650 million cubic yards of material, producing much more powerful waves.

A working group of scientists hopes to refine models of the potential Barry Arm landslide, drawing a clearer picture of when it might occur and whether it would be likely to take place as a partial or gradual collapse, which would produce a smaller tsunami with primarily local effects.

An uncertain forecast

Landslides are sometimes preceded by warning signs — geological shifts that can be picked up by seismometers. However, there are no seismometers around Barry Arm. DGGS hopes to place solar-powered monitoring equipment around the area, Masterman said. Ground temperature sensors could also yield valuable information, Wolken said. Members of the public are also asked to share photographs or other documentation gathered around Barry Arm, which may help researchers understand how the site has altered over time.

However, an absence of seismic activity doesn’t mean that an area is safe, Wolken said. Even in the absence of seismic activity, a catastrophic landslide can still take place. There’s also no guarantee that other large landslides aren’t forming at undetected sites around the state.

“Alaska is a big place,” Wolken said. “This is a thing that we’re constantly confronted with. It’s difficult to make assessments of landslide hazards over such a large area.”

As glaciers continue to retreat across Alaska, the problem of slope instability will likely grow, Wolken said. A group of researchers, including Wolken and another DGGS scientist, is seeking funding for a large-scale assessment of landslide hazards around Southcentral and Southeast Alaska.