Back on a rainy summer day in 1992, my wife Sue and I were browsing through the old Cordova Museum.

It featured a crowded, eclectic collection from Cordova’s past, varying from The Cordova Times’ original press, to a large sea turtle thousands of miles off course that was somehow caught by a local fisherman.

In fact, one of the museum’s delights was that no matter how many times we visited, there was always something new to be discovered amidst the displays in its cramped confines.

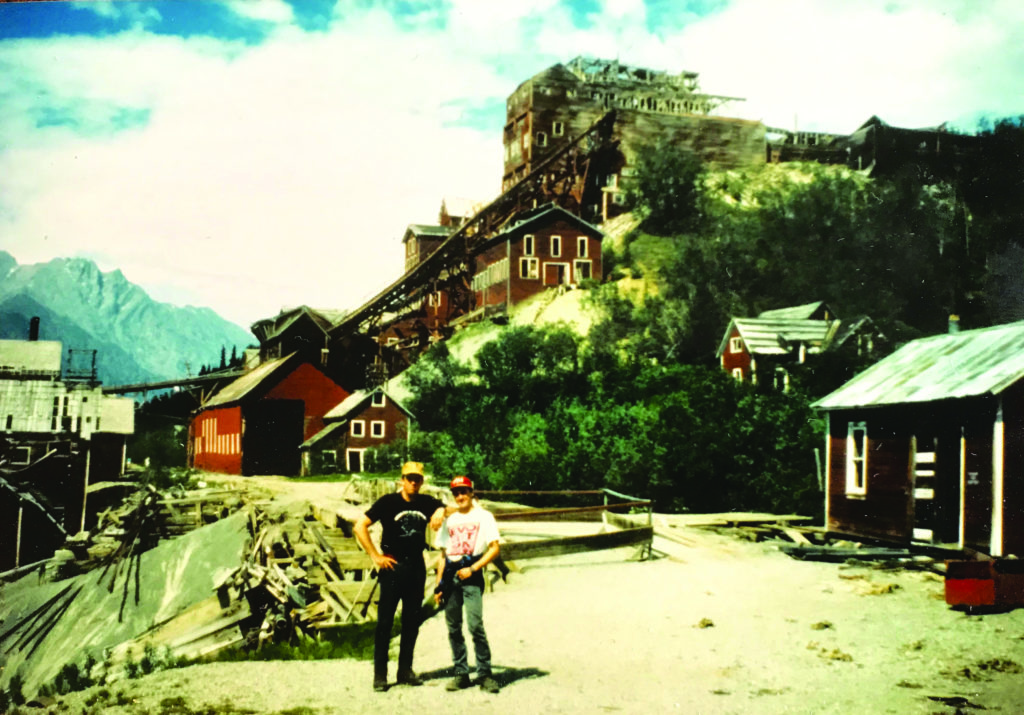

On this particular day, we were looking at old photos of the copper mines at Kennecott. Just a year earlier, Mike McHone, his son Jeff, and I had taken the ferry to Valdez, driven all the way to McCarthy, and then taken a shuttle bus ride up to the massive processing facilities at the base of the mountains.

The only way to truly understand and appreciate the scale, magnitude, and incredible engineering of the railway and mining operations is to visit this site. As part of our excursion, we hiked up to the Bonanza Mine, stayed at the Kennecott Lodge, and rummaged through all the old buildings, which at that time were still open to access without restrictions.

The tram system used to ferry supplies up to the mines, and then bring ore back down, was mind boggling. One cannot count the number of times on the trek up to the mine that we found ourselves saying, “How in the world did they get all this up here?”

In 1916 the tram handled about 400 tons of copper ore per day.

The entrance to the Bonanza mine shaft was boarded off, but a local at the McCarty Lodge told us that at one time you could walk all the way through to the other side of the mountain, and feel the wind blowing from one end to the other.

Scattered near the entrance were pieces of copper ore, which reminded me of days back in the early 1950s, when as little kids we would find similar chunks near abandoned railway tracks by the Powder House and sell them from a little stand to tourists who arrived on Alaska Steamship.

Near the shaft entrance were the faded remains of a large abandoned three-story wood frame building that had been painted in the classic red of all the Kennecott structures. Scattered amongst the debris nearby were animal bones, which we finally deduced came from quarters of beef sent up to feed the crews which worked at the mines.

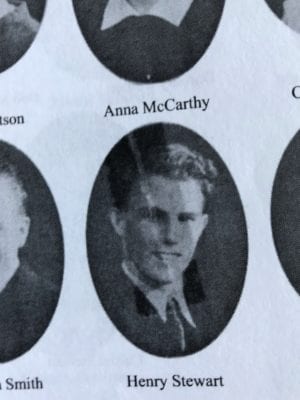

Midway through our discussion about the mine photos, who walked around the corner to confirm our observations but Henry Stewart, a longtime Cordova fisherman and boat builder.

Little did I know that Henry, who was born and raised in Cordova, graduated from Cordova High in 1937. And worked for a year at the Kennecott Mine before it closed in 1938.

What followed was a 30-minute visit about the mine operation, which Cathy Sherman, museum director, could overhear from her nearby office, and later said she wish she had recorded.

“There was no monkeying around,” Stewart said. “We lived in the housing complex, and the only days off were Thanksgiving and Christmas. There was no drinking and no gambling. If there were any disputes or disagreements, both miners were fired, period.”

Strangely, one of the things Stewart remembered most was lunch breaks down in the mine shafts.

“By then, most of the top-grade ore had been removed,” he said. “In the process, there were several huge open areas inside the mountain. For lunch, the cooks, wearing white uniforms, would ferry the lunch to us on railway carts after bringing it down the shafts.”

“Large wooden picnic tables were set up in the open area, and we would line up our mining helmets, with burning tungsten lanterns, on the tables, as they served us lunch.”

To this day, I regret not asking Stewart what he did after the mines shut down. It would have been worth at least another 30 minutes.

At the beginning of World War II, he joined the Army Air Corps and became a tail gunner on a B17 bomber. Candidates for that terrifying job had to be small and athletic to crawl through a tunnel into the bubble at the tail of the massive plane, as well as keen-eyed and well-coordinated to fire twin 0.5-inch machine guns at attacking aircraft.

In eighth grade, Stewart had decided to become a naval architect, and he paid his own way to obtain a degree from Westlawn Institute of Technology in New Jersey.

Like many Cordovans, razor clam digging was one of his many ventures, and over his lifetime he dug over 100,000 pounds.

Stewart also pursued a career in fishing, and while maintaining his boat, accidentally cut off the tips of fingers of his right hand. He proceeded to marry his nurse, Leona Hiemstra, in 1950.

They moved to Port Angeles, Washington, and then settled in Poulsbo in 1957, where he built wooden boats in the winter and fished in Alaska in the summer.

Among the marvelous craft Stewart designed and built was his own seiner, the Sea Hunt, which was undoubtedly the most attractive and well-maintained vessel in the Cordova fleet. Les Maxwell’s Bear Cape, and then Icy Cape, were other examples of Stewart’s outstanding craftsmanship.

Stewart passed away in 2014 at age 94.

For many summers, my wife Sue worked at the Cordova family grocery story, K&E Foodland, where Stewart bought his supplies. Both he and Sue’s father John Ekemo were of Norwegian heritage and may have even shared a few jokes about Swedes.

She remembered him as a quiet and meticulous shopper.

That, like so many Cordovans, lived a full and amazing life.