The North Cloud, a 105-foot power barge purchased from Army surplus, departed Cordova on Sunday, Feb. 20, 1949. It was bound for Seattle shipyards to be outfitted for fish processing cold-storage operations in Alaska. Aboard the craft was a skeleton crew consisting of new owner Fred Howard and his wife, their son-in-law Robert Zentmire, and engineer Leonard Holeman.

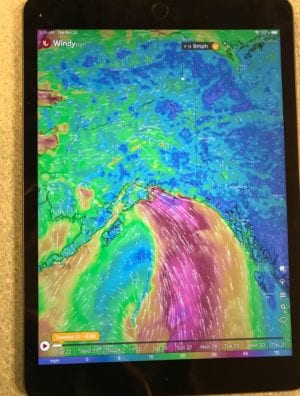

Running vessels from Cordova to Seattle requires a challenging 350-mile crossing of the Gulf of Alaska before reaching Elfin Cove and the sheltered waters of the Inside Passage.

The Gulf is notorious for bad weather conditions that can develop rapidly, and many a Cordova fisherman can recount just such challenging circumstances while bringing boats, often newly built, up from shipyards in the Seattle area.

Compounding the perils of such crossings is the lack of few safe places to find shelter when storms suddenly come up. It is no surprise that many a ship has met its fate along this particular stretch of coastline.

Back in 1949, meteorology was certainly not the detailed science it is today. Only five years earlier, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces, rolled the dice on a predicted small window of weather to launch 7,000 ships and massive forces for the D-Day Normandy Invasion across the 100-mile-wide English Channel.

He was lucky, as, soon after, bad weather commenced.

The crew of the North Cloud wasn’t so fortunate.

What the area weather forecast was on Sunday, Feb. 20, 1949 is unknown, but it didn’t take the crew of the North Cloud long to find out they were in dire straits.

By early Monday morning, after taking a beating in a major storm, they had been blown ashore somewhere just outside of Cordova.

It wasn’t until early afternoon on Tuesday, Feb. 22, that news of their mishap reached Cordova.

Written reports of the shipwreck first appeared in the Wednesday, Feb. 23, 1949 edition of the Cordova Times.

Back then, the Cordova Times came out three times a week, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Colorful Editor Everett Pettijohn, well known for his dramatic flair, was the perfect wordsmith to report events that would continue for over a week.

Here are excerpts of his first account, based on an interview with the North Cloud’s engineer, Robert Zentmire.

“Gales, snow and sleet impeded the voyage throughout the night and a heavy southeaster finally drove the craft ashore at 5 a.m. Monday”, wrote Pettijohn. “During the gusts, spray and waves went over the pilot house. The deck iced up to a depth of two feet. A small space about a foot square was kept open on the pilot house windows by periodic placing of hot water bags. With only one engine of the twin-screw craft in operation the added assault of the high gusts required two men to hold the ship. At one violent surge, the wheel was flipped out of Howard’s hands striking him a hard blow of the wrist, shattering his watch and leaving a painful injury.”

The North Cloud was grounded on a gradual sandy beach, receiving a fierce pounding from Gulf of Alaska breakers.

Without getting off a mayday.

Not mentioned in the Cordova Times reports were any attempts to make such a radio call. Maybe there was no such equipment on board, or perhaps it had been knocked out of commission. Nor was any reason given for only one engine in operation.

Not only was the crew uncertain of their whereabouts, no one else was aware of their circumstance. How would any rescue attempts begin, if no one knew they were marooned?

However, there was hope. The report did not make it clear if the weather had abated, but at least it had to soon be getting lighter outside. Sunrise on Feb. 21 was around 8 a.m.; sunset about 6 p.m.

No one had suffered serious injuries.

And before daybreak, Holeman, who would soon be one of the heroes in this saga, had taken a bearing of 137 from north on a rotating nighttime beacon.

Given the short amount of time they had been at sea, it had to be the light on the tower at the CAA Mile 13 airport station.

At 9 a.m., four hours after the grounding, Holeman donned rubber boots and warm clothing, jumped off the barge, and headed for help.

Coming up next week, part two of the North Cloud Saga: A Herculean Trek.