A heat wave that impacted the marine food web of the Gulf of Alaska in 2014 officially ended in 2016, but federal fisheries scientists still don’t know if that ecosystem will revert to pre-heat-wave conditions.

“As of 2019, the Gulf of Alaska ecosystem had yet to recover from the effects of this major heat wave,” said Rob Suryan, program manager with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, and lead author of a new NOAA Fisheries study. “What also is remarkable is how rapidly conditions changed and that species from all trophic levels and age classes responded. The community composition, or proportion of species that make up the ecosystem, are distinct from what we observed prior to the heat wave.”

The report on lingering effects of the heat wave on coastal and marine ecosystems notes that, by 2016, the percentage of global ocean experiencing strong or severe heat waves had increased to nearly 70%. Also documented was an increase in disturbance to marine ecosystems, biodiversity and ecosystem services associated with marine heat waves. The heat wave proved particularly strong in the Gulf in terms of spatial extent, duration and magnitude of ocean warming. What was also unique, researchers noted, was that it extended to the seafloor, affecting diverse habitats, and its impact was seen in offshore oceanic to intertidal waters in glacial fjords.

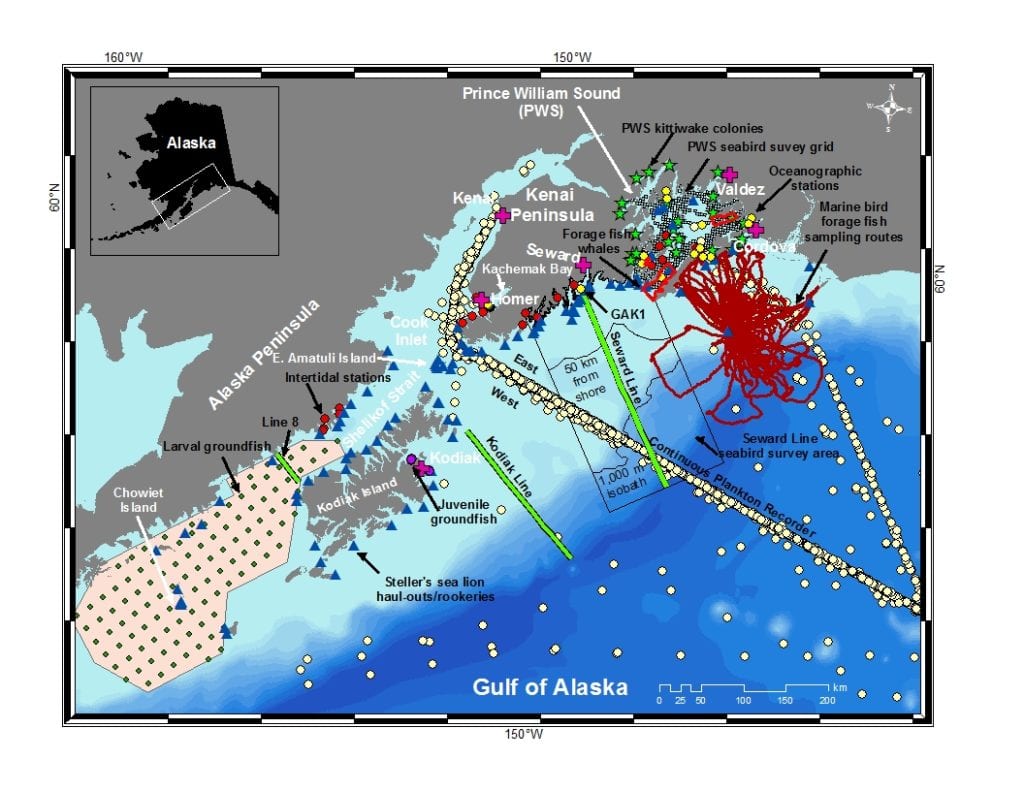

Researchers examined dozens of biological data sets from different sampling programs in the Gulf, along with long-term monitoring and synthesis efforts led by the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill Trustee Council’s Gulf Watch Alaska, a long-term ecosystem monitoring program, and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. They also tracked whether species sowed continued response to the heat wave or signs of recovery for up to five years after the onset of the heat wave.

They looked at species abundance, size, growth rates, weight and body condition, reproductive success, and species composition before, during and after the heat wave.

They found that about half of these indicators showed an abrupt change during and a prolonged response after the heat wave ended. Even by 2020 some of those Gulf indicators had yet to recover.

Those warm-water anomalies persisted for at least four to five years after the heat wave began, especially in the lower water column of the continental shelf. That meant that various life stages of many organisms experienced above-average warm conditions for up to five subsequent years and concluded that this likely contributes to the lag in returning to pre-heat wave values for the overall Gulf community.

While some species did return to pre-heat-wave levels soon after the heat wave, others from intertidal algae to whales did not. “These results signify the magnitude of the heat wave and suggest the Gulf of Alaska ecosystem had passed a tipping point that could no longer be buffered by resiliency in the system,” Suryan said.

Who were the winners and the losers?

Indicators with primarily negative responses were phytoplankton, intertidal organisms, forage fish, adult groundfish, pinnipeds and piscivorous seabirds at haul-outs and breeding colonies, and commercial fish, especially Pacific cod and sockeye salmon.

Humpback whales in the northeastern Gulf of Alaska showed a precipitous decline during the heat wave and remained low through 2019. Warm-water-associated zooplankton abundance had a positive response and stayed positive even as the water column cooled the year after the heat wave, and cool-water-associated zooplankton did not show a marked decline during the heat wave.

Commercial fish harvests with positive trends included chum salmon, sablefish, Coho salmon and Pollock, with regional variability among ports, researchers said.

Other Gulf life showed only short-term, or no detectable, response, including phytoplankton bloom timing, phytoplankton size, forage fish growth and condition, and at-sea densities of highly mobile seabirds.

After the heat wave ended there was a re-intensification of the warming through the fall of 2018 and summer of 2019. Spring chlorophyll size composition and warm water copepod abundance returned to heat-wave levels in 2019.

The research report also noted that recent warming events that began with the eastern Pacific marine heat wave appear to still be affecting most of Alaska, including the Gulf of Alaska, the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean.

Researchers said they hope to continue studying changes in the Gulf ecosystem this year.