Timber workers often take the brunt of criticism for damage to spawning habitat in rivers and streams running through timberlands, when in fact many have fought to restrict timber harvests and protect the habitat.

In his chronicle on the history of conflict in the timberlands of the Pacific Northwest, author Steven C. Beda, an assistant professor of history at the University of Oregon, speaks of tree fellers and others in that industry who told him of their connection with these forests, where they have fished, hunted foraged and hiked all their lives.

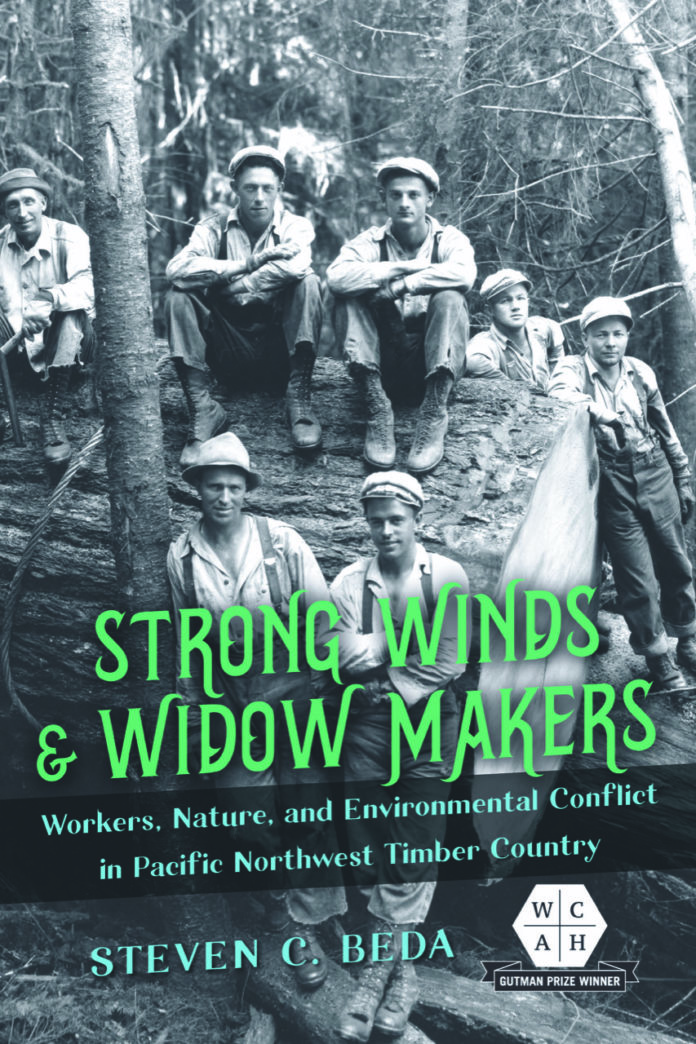

In his new book, “Strong Winds and Widow Makers,” Beda takes a sympathetic look at the human beings who see these forests as a vital part of themselves and want to protect the habitat, even though they fell trees for work.

The book title is a reference to the challenging winds and loose limbs of trees being logged, which can fall suddenly, killing those below. Hence, the widow makers.

Rather than distancing working-class communities from the environment, life in the industrial woodlands has created deep connections among timber workers, their families and the forests, making them intensely aware of their obligation to the forests. This close relationship with the environment is akin to that of people living in coastal fishing communities and their marine environment.

While the book does not mention Alaska, the historic conflict between the timber industry and environmentalists in Washington and Oregon is similar to incidents in Southeast Alaska where salmon habitat has been adversely impacted by timber harvests.

Beda’s book, published by the University of Illinois Press, is a volume in the series The Working Class in American History.

Beda’s research stretched back to the Great Depression, a time when timber companies employed local loggers to clear cut forests, then moved on, leaving once robust forests looking like a war zone after the battle ended. Most lumber companies responded to the stock market crash in 1929 by shuttering their camps and mills, from Oregon and Washington to British Columbia, and men lucky enough to keep their jobs were paid far less than before the Depression hit.

The book is available in hardcover and paperback editions.