A couple weeks ago, while waiting for my studded tires to be swapped out at Anchor Auto, I wandered across the street to check out the latest changes in the fishing fleet. With another season about to get underway, the harbor was filling up with bow pickers and seiners.

Along the way, I happened into the Fishermen’s Memorial, which I confess to having bypassed more than once in a hurry to get out for halibut or subsistence fishing.

It was a sunny day, and half an hour later I realized my truck was likely ready. Time had slipped by while studying each of the 118 Memorial Plaques attached to the railings that surround Joan Bugbee Jackson’s inspiring statute of a rain-battered fisherman steering into heavy seas.

Having lived in Cordova all my life and worked on tenders or crewed on seine boats for years dating back to the early 1960s, it was hard not to be lost in memories inspired by these tributes to so many famous local fishermen. Each plaque had a story to tell, and indeed, as is often the case with those who go to the sea, each of the bygone was a master storyteller.

Many of the plaques had tidbits I did not know. For example, I was quite surprised to learn on the plaque memorializing Charlie and Violet Simpler, that Violet had gone out for eight years as cook on their small seiner the Vecci, and her most popular onboard meal was chicken and dumplings.

That was an entertaining fact to discover because I crewed in a similar role for three years on the Simpler sequel to the Vecci, a much larger 46-footer named the Pt. Countess, and fortunately not once did attempt that particular dish.

Yet the plaque that fascinated me the most was a tribute to The Mayor of Kiniklik.

No, Cliff Alber had not been elected to this office. The term is used in this context to signify a fisherman who spends his whole season at one particular spot, learning the secret nuances of time, tide, currents and hidden underwater obstacles, as well as their impact on the flow of salmon in that area.

In some cases, this has actually led to the names of places. For example, on the Copper River Delta, several sloughs bear the names of early fishermen who camped and set netted on the banks of various waterways. Tiedeman, Pete Dahl, Gus Stevens and Whiskey Pete are examples.

Kiniklik is the name of a small abandoned Native settlement on the tip of the peninsula separating Eaglek Bay and Unakwik Inlet. A chart of Prince William Sound shows five small black squares there, indicating the location of former buildings whose history is a mystery.

“It’s a beautiful location, with a sheltered harbor, and a perfect place for subsistence on salmon and clams,” said Mark King, of the Native Village of Eyak. “Yet very little is known about it.”

Louie Alber, along with his sister Lyne, who as youngsters crewed on their dad’s seiner, recalled exploring the area, and finding parts of an altar in what must have been a Russian Orthodox church at the site.

Louie also recalled learning to work at a very early age, in a very remarkable endeavor.

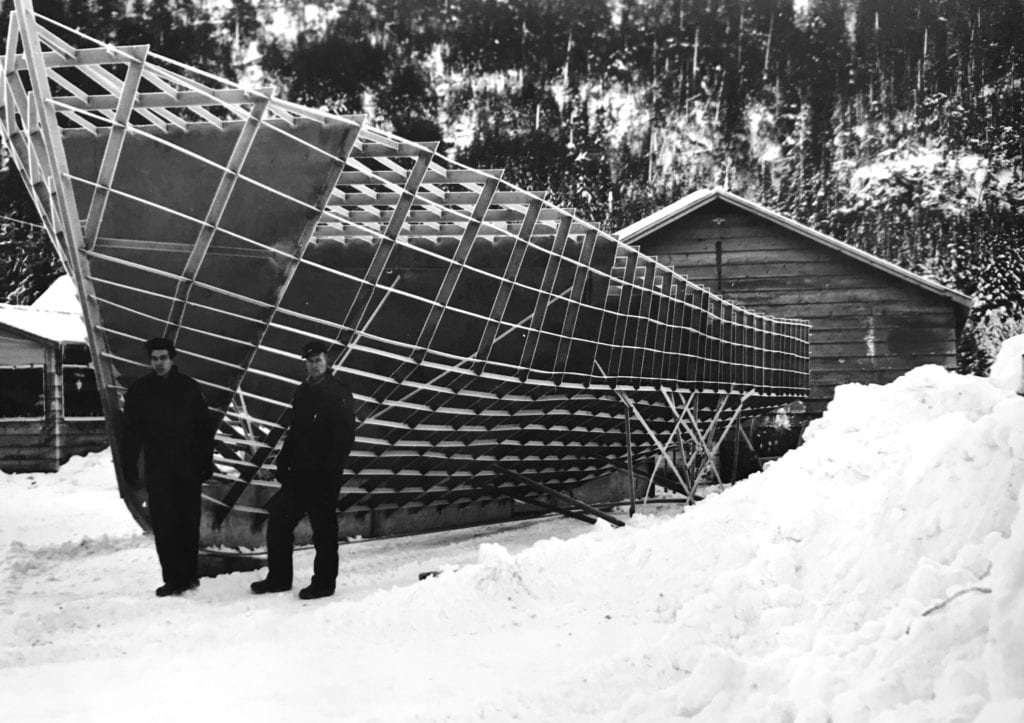

In the late ’60s, while he was 8 and Lyne was 10, Cliff and his neighbor Louie Barnes took it upon themselves to build steel fishing boats in their front yards down in “Old Town,” which was located on what is now known as Chase Avenue.

Cliff had apprenticed in the welding trades in a shipyard in Oregon, and for two years the duo labored to create massive 58-foot vessels, known as “limit” seiners because of restrictions on any bigger size boats.

Many Cordovans made it part of their weekend ritual to drive past this amazing undertaking, which Louie Alber described as in “their front yard, because there was no backyard.”

Guess who ended up using pointed hammers to “clean up and knock the slag off” the welds on the inside of the intricate superstructure?

Cliff’s young apprentices.

“It was pretty challenging climbing around the framework. Dad believed in the work ethic,” said Louie Alber, who mentioned that when he and his sister were out fishing, they were already taking turns stacking web as the seine came through the power block.

As part of the construction project, the completed hulls had to be pulled out of shelters to add the basic cabins on top, and one classic family photo shows Cliff’s wife Marybeth standing beside her husband’s huge hull, with a caption in her handwriting on the bottom saying, “But I still say it will never float.”

Considerable ingenuity was required to get the incomplete vessels to the harbor.

“They cut double-tired axles off old dump trucks, welded them to the bottom, and had Guy Beedle tow them off with a frontend loader,” Louie Alber said.

In March 1971, Cordovans lined the streets to watch this unusual parade, which included deck hands standing atop the cabins to lift wires hanging across the streets out of the way.

The boats were launched right below the site of Ray Shipman’s Harbor Hydraulics, and local master craftsman Frank Steen did all the finish woodwork on the cabins and elsewhere.

For years, Alber’s Miss Lyne and Barnes’ Due North were the biggest seiners in the fleet.

Louie Alber also remembered an unusual recognition for his dad’s handiwork.

“In the late ’70s, Alaska Airlines, as a publicity stunt, had a Biggest Brag Contest,” he said. “Dad won third place and a $1,000 prize for his entry, which was ‘Built a 58-foot steel boat in my front yard’.”

For many a season, Kiniklik became its second home.

Eventually Louie Alber moved on to work on other boats, and Cliff sold the Miss Lyne, to finish up his fishing career gill netting the Flats, before passing away in 2004.

Louie has gone on to become a very successful highliner, and by no coincidence, now owns a beautiful fiberglass 58-footer of his own, the Leading Lady.

Louie Alber recalls his dad’s proudest achievement, and no, it wasn’t building a boat; it was “that I taught my kids to work hard so they would always have a job.”

For anyone who has worked on a seiner and made 19 to 21 sets a day, the Memorial Plaque to Cliff and Marybeth Alber says it all:

3 a.m., time to pull the hook.

1st on the point.

Sunset last jumper on the inside.

Time to close up.

WYZ2781, Miss Lyne out.

Proof of that lesson is on the very plaque by the Fisherman’s Memorial.