Sometimes there are no easy answers. What is to be done about the stretches of the Copper River Highway that have been washed away by rising waters, or the bridges half-demolished by earthquakes? How about the Million Dollar Bridge, a landmark currently in danger of being irreparably damaged by drifting icebergs? Like it or not, these decisions are now up to you.

The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities has asked Cordova residents to weigh in on a series of proposed plans to repair the Copper River Highway. Optional plans were outlined in a draft Planning and Environmental Linkage study published Dec. 17. Until Jan. 17, residents can voice their support for a particular repair plan, or suggest new ideas, by emailing jeff.stutzke@alaska.gov.

“There’s nothing cheap about any of these ideas,” said William Kulash, DOT environmental impact analyst. “This is incredibly expensive — there’s no mistake about it. But there would be millions of dollars spent to abandon this highway also. So, how do you want that money spent?”

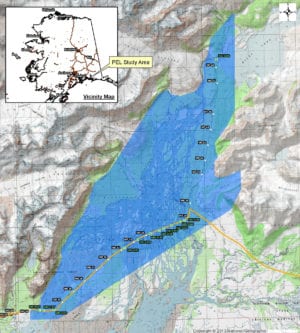

The cash-strapped DOT has no immediate hope of repairing the Copper River Highway. However, the PEL study will prepare a well-researched plan to be put into action as soon as funding comes available. The study covers an area located roughly between mile 27–51 of the highway, which includes 12 bridges.

Keeping the Copper River Highway in sound condition is “problematic at best,” according to the study. However, decaying bridges and roads have had an outsize impact on commerce by discouraging tourists and diminishing access to hunting and fishing areas. Additionally, vital research on salmon migration, conducted by Native Village of Eyak and the Department of Fish and Game, has become far more costly and complicated as roads have deteriorated.

The curious case of Bridge 339

The urgency of rebuilding the Copper River Highway is made clear by the case of Copper Delta Bridge No. 339. Bridge 339 is — or was — a 401-foot, concrete-decked structure connecting two banks of the river. It was closed in August 2011 after DOT engineers found that areas of the riverbed had been scoured away, undermining the bridge’s support piers and compromising its structural integrity. The following year, before repairs on the bridge were completed, the river washed across the highway at the bridge’s east end, completely eroding a section of the roadway. And, although the scour holes in the riverbed have since filled back up with sediment, Bridge 339 remains too rickety to withstand an earthquake.

So, what will we do about Bridge 339? The PEL study offers several solutions, such as building an all-new, 1,540-foot bridge to span the washed-out area of highway, extending the existing bridge or even building a cable-car line over the gap.

“Some of them are good ideas, some of them aren’t,” Kulash said. “Hopefully, we can whittle ‘em down.”

It would also be possible to restore the washed-out section of road, or to build an entirely new, 1.25-mile road going around the washed-out area. As a rule, building a road is cheaper than building a bridge. The PEL study estimates that a new road could be built for as little as $2.79 million, whereas a new bridge could exceed $50 million, depending on the design.

Should the DOT build a new road, extend the existing bridge, build an aerial cable car, or try something altogether different? For better or worse, the choice is now yours.

The million dollar fixer-upper

Most wear and tear on bridges is due to the powerful and ever-shifting currents of the Copper River. However, the Miles Glacier Bridge, better known as the Million Dollar Bridge, is a special case.

One thousand five-hundred fifty feet long and rising 30 feet above the water, the Million Dollar Bridge began its life carrying shipments of copper from the Wrangell Mountains. In 1938, when the Kennecott Copper Corporation stopped mining, the bridge was abandoned. It wasn’t until 1962 that the decaying railway bridge was converted into a highway bridge, according to DOT documents.

Two years later, the catastrophic Good Friday Earthquake jostled around the bridge’s spans by more than 12 feet in some places, shearing off the northmost span and plunging it into the water. Restorations were made to the Million Dollar Bridge’s popped rivets and fractured concrete in 1973, although these were again damaged by high water events in the ’90s, according to the PEL study. Today, the Million Dollar Bridge is both a nationally recognized landmark and a decrepit hulk.

Icebreakers were installed near the bridge’s first and second piers to protect them from collisions with icebergs floating downstream from Miles Glacier. However, in August 2016, a large iceberg struck the icebreaker protecting the bridge’s first pier. The damaged icebreaker was pushed downstream during a 2019 high water event, and now offers the bridge about as much protection as a layer of wet tissue paper. Compounding this, computer analysis shows that the first and second piers, built with unreinforced concrete of inconsistent quality, are vulnerable to failure, according to the PEL study.

Every option for repairing the Million Dollar Bridge would require moving heavy equipment to the bridge site, currently inaccessible by land. In light of this, you may ask — if keeping the bridge from falling into the river is such an impossibly complicated and costly undertaking, why not just let it fail?

The PEL study provides the answer: because cleaning up after a collapsed Million Dollar Bridge would probably cost more than fixing it. If the bridge fell into the Copper River, it would seriously interfere with the natural environment, and create a wave that could inundate or destroy infrastructure at the Forest Service’s Childs Glacier Recreation Area and at the nearby Childs Glacier Lodge. Additionally, some paint used on the bridge contains lead, Kulash said.

Several options for a new icebreaker are presented in the PEL study. New icebreakers could consist of 12-foot-thick steel shafts, of concrete slabs or even a pair of concrete islands that would shield the first and second piers. Here, again, Cordova must choose how its tax dollars will be spent.

What now?

The DOT’s research also uncovered 25 aged or damaged culverts in the area. These culverts are probably inadequate to allow salmon through, cutting off miles of spawning territory, according to a Department of Fish and Game study. Potential ways to replace these culverts are among the other infrastructure issues outlined in the PEL study.

As DOT funding shrinks, it becomes increasingly unclear when the tens of millions of dollars necessary to repair Bridge 339 or the Million Dollar Bridge will become available.

“We recognize that there are issues here, that there’s a need,” Kulash said. “We’re gonna go after money. We’re trying to be proactive.”

Native Village of Eyak has also applied for a federal grant to repair the washed-out road near Bridge 339. The plans now being drawn up with public input will, at least, make sure that the DOT is ready to act quickly when funding is obtained.

“As engineers, we try and make things work,” said Jeff Stutzke, DOT regional hydraulics engineer. “But I’m not a resident of Cordova. I don’t live there day-to-day. It’s a much different perspective that you have, living in the community, than someone like me. So, it’s so important for us to get the broadest perspective we can… We don’t want to leave any stone unturned.”