By Nathaniel Herz

For the Northern Journal via the Alaska Beacon

I’d been hearing and reading about Yakutat’s logging controversy for two years before I finally decided to buy a plane ticket to town last month.

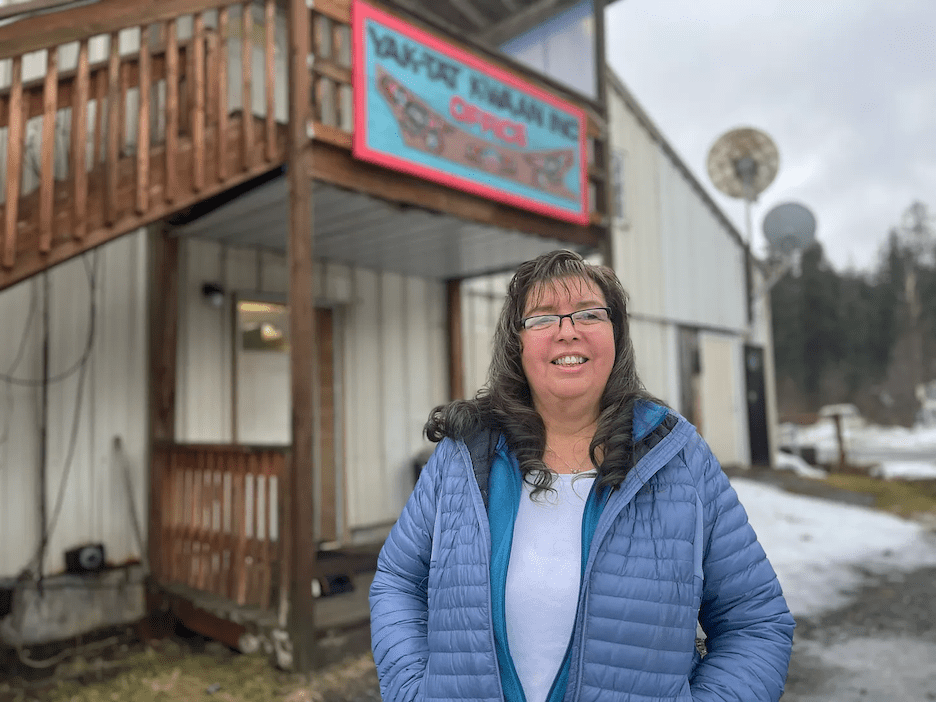

The Alaska Airlines jet landed at dusk, and the next morning, I woke to find that my bed and breakfast was perched above the bright green waters of Monti Bay, and I drove along the shoreline in my rented SUV to the modest offices of Yak-Tat Kwaan, the village corporation.

Shari Jensen, the chief executive, met me outside and showed me into her office, lined with maps, to talk about the corporation she leads.

The Kwaan, as it’s known, was established in 1973 after passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. That legislation, approved by Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon, extinguished Indigenous Alaskans’ land rights in exchange for nearly $1 billion and some 10% of the acreage in the state.

Yak-Tat Kwaan was entitled to 23,000 acres, or 36 square miles — a tiny fraction of the traditional homelands of Yakutat’s Native people.

Those 36 square miles, however, did contain a valuable resource: trees. Even after the corporation logged some of its lands in the 1980s and 1990s, as part of a partnership called Koncor Forest Products, a 2001 survey of just one-fourth of the Kwaan’s property estimated its remaining timber value at $35 million.

Today, the Kwaan is led by a nine-member board elected from, and by, its Indigenous shareholders. Jensen, the chief executive, told me she wants the corporation to diversify into ecotourism.

But the Kwaan lacked the capital needed to launch such a business, which is why board members looked to timber, according to Jensen. Cutting trees was a way to create jobs, generate profits and pay for heavy logging machinery that the corporation could also use to build housing and tourism infrastructure, Jensen said.

Jensen said carbon credits revenues would have trickled in too slowly, and that such deals wouldn’t have created local jobs. So, in 2018, the Kwaan launched a subsidiary, Yak Timber.

Borrowing for start-up costs

To acquire logging equipment and pay start-up costs, Yak Timber borrowed millions of dollars. Documents filed with state agencies in June show more than $10 million in loans that haven’t come due, and the company has pledged its logging equipment and timber rights as collateral to its bank, Northwest Farm Credit Services.

The Kwaan could have limited the borrowing by teaming up with an investor or an established logging business. But in interviews, board members said they were skeptical of bringing in outsiders because of the corporation’s experience with Koncor Forest Products in the 1980s and 1990s.

Many of the Kwaan’s critics told me they’re not opposed to all logging — just harvests that threaten areas they value for subsistence, recreation and the potential they could hold cultural or archaeological relics.

“I am not against logging when logging is done properly,” said Marry Knutson, who works for Yakutat’s tribal government. “My only motive is to protect our culture.”

The opposition has left Yak Timber with limited options to continue cutting trees, and to satisfy the bank that financed the timber operation, Jensen, the Kwaan’s chief executive, told me.

Meanwhile, over the objections of tribal and cultural leaders, Yak Timber had been logging at Humpback Creek — the salmon stream acquired by the Kwáashk’ikwáan clan centuries ago.

Kwaan board members had downplayed the historic and cultural significance of the Humpback Creek site. But in early December, an anonymously run social media account, Defend Yakutat, posted a photo that it said was taken there by a Yak Timber employee.

It showed a previously undiscovered stone wall.

In an announcement shortly afterward, an archaeological expert said the discovery could reveal a “unique record of traditional lifeways and subsistence practices extending back 700 years.”

The harvest

Since Yak Timber began cutting near Humpback Creek, a caustic fight has erupted in Yakutat over the site’s significance.

Opponents point to the creek’s symbolic value to the Kwáashk’ikwáan clan, and say that the absence of previous archaeological discoveries is far from proof that there’s no evidence to be found.

“Technology has changed over time,” said Knutson, the Yakutat tribal government employee. “And that’s why the exploration of this area, by archaeologists, is important.”

Knutson, when I interviewed her, said the tribal government bears some responsibility for the lack of modern research in the Humpback Creek area, which could have been funded by grants. But its resources are limited, she added, and the tribe has prioritized efforts like developing housing in Yakutat’s tight market.

“We have to take care of our people that are living right now in order to take care of our ancestors,” she said.

The tensions over logging at Humpback Creek reached new levels in December, with the anonymous Defend Yakutat account’s publication of the rock wall photo.

A week later, Yakutat’s tribal government, along with Sealaska and its cultural arm, Sealaska Heritage Institute, issued a statement calling on Yak Timber to stop logging in the area. The groups cited Defend Yakutat’s report of “several house pits and a series of parallel stone walls laid across a dry creek bed.”

The stone wall is “clearly a cultural feature” that was probably part of an Eyak settlement in the area, said Aron Crowell, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center who’s worked at several sites near Yakutat and collaborated with the tribal government.

“From my own experience, and many others’, it’s not that easy to find sites in a forest,” Crowell told me. “I think in the end, it will prove to be one of the most important archaeological sites in that area.”

A tree’s value

At the end of my conversation with Marvin Adams, the Kwaan board member and head of Yak Timber, I asked another burning question that I’d heard from a number of shareholders: Why lead his Native corporation into the timber industry when logging is on the decline nearly everywhere else in Southeast Alaska?

It seems like there are too many systemic forces arrayed against Yak Timber for it to succeed, I said to him.

Executives at other Native corporations say that younger shareholders seem to value cultural preservation over logging, mining and whatever else constitutes “resource development.” The U.S. Forest Service, through the Roadless Rule, limits logging on federal holdings. And Southeast landowners are increasingly getting paid for carbon credits — leaving trees standing rather than cutting them down.

“I think if you’re an environmentalist, you probably think that. But if you’re a business person, you probably wouldn’t,” Adams said.

The Kwaan’s push into logging may now be facing its most significant challenge.

A group of dissident shareholders is set to launch a recall campaign seeking to depose the corporation’s leadership.

In the days following my trip, I heard from multiple people in Yakutat about a possible thaw in tensions between the Kwaan and the village’s tribal government, which has stridently opposed logging in the Humpback Creek area.

Tribal leaders, up to that point, had not been able to access the site to look for archaeological evidence and examine the discoveries publicized by Defend Yakutat. But discussions between the two sides were taking place.

A week ago, though, photos quickly circulated among village residents that show freshly logged areas near Humpback Creek, along with heavy equipment near the edge of the bay. Tribal leaders saw that as a huge setback.

Jensen, when I followed up with her by phone last week, acknowledged that Yak Timber has continued logging at Humpback Creek to satisfy its bank, “until we can come up with a new plan.”

But she saw the harvest in a much more positive light, and sent me a different photo from the same area — showing neatly stacked logs, a few stumps and a scenic backdrop of ocean and snow-covered peaks.

“One day, that will be valuable land if we want to do something with tourism,” Jensen told me.

Logging critics, she added, say they want to keep the trees standing for future generations of shareholders.

“But a tree,” she said, “is not going to put a house on the land, or food on the table.”

A longer version of this article was originally published in Northern Journal, a newsletter from journalist Nathaniel Herz. Northern Journal can be found at natherz.substack.com.