By Julianne Parker

George Olsen passed away Saturday night. The following story includes an interview with Olsen in 2014, and is running this week in honor and celebration of his memory.

The Olsen’s home is across from the new elementary school built just above Main Street. If you follow the road down its steep decline, you’ll reach the harbor where the docks are lined with fishing boats and the gulls squawk mercilessly—lured to the salty stench of the day’s catch being hauled in. If you continue up the road, you’ll climb to the top of one of the many mountains whose bases Cordova nestles in. You can just barely make out their peaks today hidden behind a thick cover of fog and a miserable wet drizzle. Today is the first day that Cordova’s more typical July weather has shown itself—the rest of my time here has been graced with blue skies and twenty hours of warm light.

“Did you notice the tops of the mountains?” George Olsen asks, gesturing out a window that on a clear day might give way to such a view. “There’s no snow on them. Usually, it’s September before we have bare mountains.”

He tells me the streams are drier than usual this season. The winter—milder. The summer—glorious, yet unusual—with longer stretches of sunshine and less rain. The fishermen, he says, are worried about next year’s salmon runs with the low water levels.

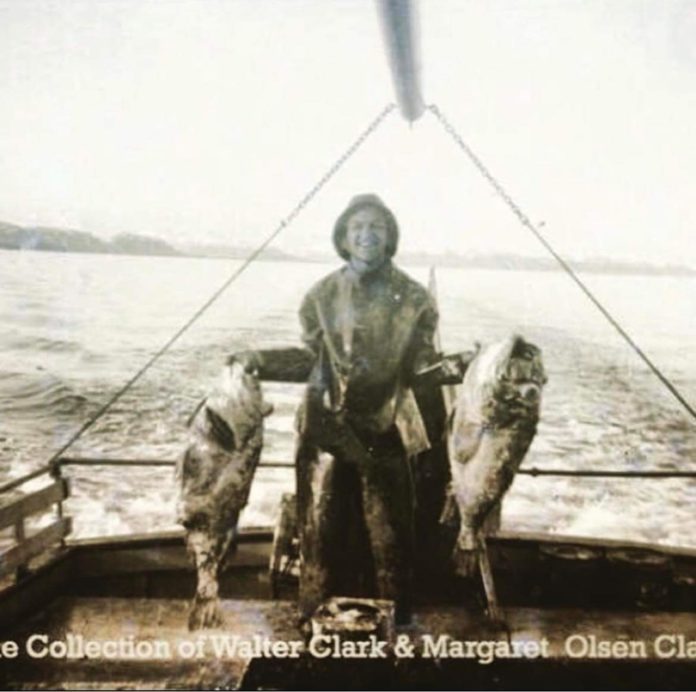

He used to be one. A fisherman, that is. Like most young men growing up in the 30s and 40s in Cordova—in the days before Alaska was proclaimed a state and before the government regulated fisheries—George worked on the decks of fishing boats in the summers. Halibut. Crab. Salmon.

“Was your father a fisherman too?” I ask.

He scrunches his brow and cocks his head ever so slightly, staring at me as if I had just asked him whether the ocean was filled with water. “Of course,” he enunciates, making clear the stupidity in asking such a question.

George is a man of anecdote and opinion. Stories fill the afternoon—digging for razor clams as a boy, or cleaning the crude oil from the Exxon Valdez spill where it spread fourteen inches deep across the water’s surface. The opinions are quick to surface next—about the people who came to Cordova to exploit the Natives for their resources, and the ones who come now to exploit them for their culture, or that the changing weather patterns are mere indicators of the world coming to its end as the Bible forewarns.

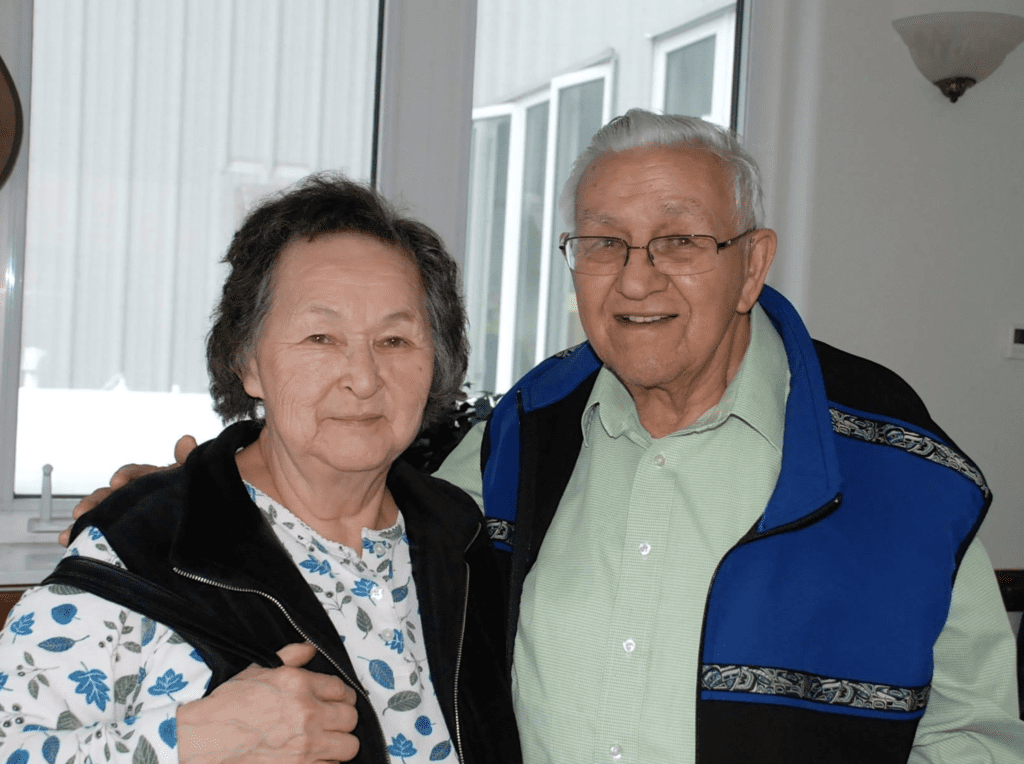

His feisty bluntness is steadied by his sweet-smiled wife who rocks their great-granddaughter in the chair across from him. Leona is an Aleut-native and has a deeper connection to her native heritage than her husband, who was never taught to speak his native tongue as she was. George has now come to the end of a rant about Native preservation being merely a business toehold for environmentalists that he chooses to not partake in. As he comes to a close, Leona raises a pointed finger and holds it in the air to keep her husband quiet. She explains the reasons for her continued Native connection and of her respect for the varying reasons people come here to protect and preserve Native traditions.

“I think the people that come…”

“And exploit the Natives!” George shouts in the background. She gives him a marital glare, dissolving his chuckle into silence, and continues.

“Anyway, people that come, people like you,” she says gesturing to me as I sit with a notebook in hand, pen scribbling across the opened page. “They come and use our story and we may never know to what extent they’ve used it. We have to live with what they say.”

I feel an immediate rush of guilt. I rush to defend my reason for wanting to speak with them, assuring the couple that their story is not meant to be exploited but to merely gain a better understanding of Native Alaskan culture and a sense of how it has changed in their lifetime.

“No dear, you’re missing the point,” she says at the end of my flustered explanation. “We have to realize that things need to advance. We can’t stay in the 1930s forever. We have grandkids that will be living after we’re gone and they’re going to live with what we told you. So, we have to be as truthful as we can be and hope that people like you tell our story right.”

I press her to explain further but the baby starts to cry and soon I’m being whisked out the door in a rush to put the kids down for their afternoon naps. Now, I’m left to decipher her words myself.

In order to advance, we must be truthful.

What kind of truth might she have meant?

I reread the notes I took that afternoon. There was a pattern. The Olsen’s didn’t speculate much on the future, but instead told stories of the past. Their stories painted images of what life was like during a time that fewer and fewer people can remember. They can describe the way their people used to live completely off of the land—the way they would hunt game in the fall and store it through the winter, the way they knew how to navigate the land for the best spots to fish the river or pick berries in the forest. They remembered times before Columbia Glacier had receded four miles, or the first time they saw the entire face of that same glacier break apart from the rest and crash down into the ocean below. They can recognize that the fireweed bloomed two months early this year, or that the blueberries didn’t grow at all. They know that the mountaintops should still be covered with snow in the middle of July.

These memories, in their exceeding rarity, are connections to the past. They can help us—the generations that don’t remember what it was like before the grocery store or the dam—identify the changes that are taking place in the environments we live in.

Amidst these great, critical discussions about science, is the inexplicable value of memory—knowledge that can easily be lost if it isn’t passed down and preserved.

Or, as Leona worries, if these stories aren’t told right.

This story was originally published on October 17, 2014 for the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication’s Science & Memory project.