Survivors of the days of the federal Indian boarding school program spoke at length Sunday about the physical, sexual, and psychological brutality suffered as children, testifying in the presence of top officials of the Department of the Interior on a mission of healing.

“Today we have the beginning of our truth-telling to the federal government,” said Liz Medicine Crow, president and CEO of the First Alaskans Institute, in an hours-long event at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. She praised her friend Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, whom she has known for many years, as “our Native sister.”

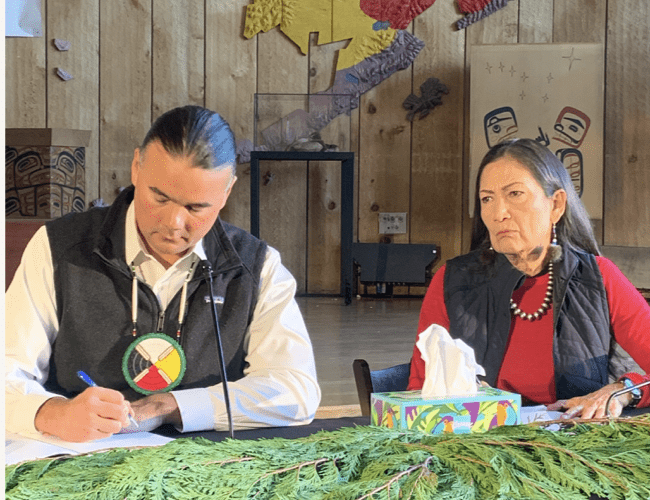

Haaland, who was wrapping up a multi-day visit to Alaska, with Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, sat solemnly at a table before several dozen Alaska Native people, intent on hearing first-hand accounts from each individual who opted to testify.

“This is a journey that we will take together,” said Haaland. “I am here to listen to all of you. I am with you on this journey. I will weep and I will feel your pain.”

The hearing in Anchorage was the 10th stop on “The Road to Healing,” to provide Native survivors of the federal Indian boarding school system and their descendants an opportunity to share their experiences as part of Interior’s Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

Jim LaBelle, a Vietnam War Navy veteran who has served as chairman of Chugach Alaska Corp., was the first to testify about the brutality he endured as a child at the Wrangell Institute, a Bureau of Indian Affairs school five miles from the town of Wrangell in Southeast Alaska.

LaBelle described the Institute as “a total prison system,” where Native children were punished for speaking their own language, had their mouths washed out with lye soap and were often made to run a gauntlet naked while other children were told to hit them with belts. Those who did not hit hard enough were themselves stripped and made to run the gauntlet, he said.

“Individuals from nearly all church groups (who were involved in running these boarding schools) were abusive we well as the employees of the BIA,” he said. “They all were abusive to one degree or another, even those who attempted to report abuses were stonewalled or shunned or fired. There was no such thing as protections for whistle blowers.”

When they arrived at the Wrangell Institute, the children, some as young as five, had their heads shaved and were given a number and were thereafter called by that number instead of their name, he said.

“We had to march everywhere,” he said. “We had to clean bathrooms and clean floors.”

There were times when the youngest children were locked out of the dorms and given pails to pick up trash and weren’t allowed back into the dorms until they had trash in the pails, he said.

There were also much more serious incidents of matrons sodomizing children and girls being sent home from the Institute after they were impregnated by adults working at there.

“It was a small campus,” said LaBelle. “They could not hide any of this from us.”

The food – a lot of powdered juice, powdered milk, and powdered eggs – made a lot of the youngsters, used to the Native foods at home, sick with diarrhea and they were punished for soiling their beds, he said. There were also cases of children who just disappeared and were never heard from again, he said.

All these years later, he and others are still processing all these generational harms, said LaBelle, the father of three children and seven grandchildren with his wife of 50 years, Susan.

LaBelle, currently the president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, also testified in May of 2022 at a federal hearing to establish the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the United States.

In his testimony there he spoke of arriving at the Wrangell Institute as a young child.

“We were taken into an open area and divided by gender. We were stripped totally naked, our hair was cut, and we were marched to the shower. Many of my classmates had never seen running water before and were frightened by the showers. One boy was hesitant to scrub his body, so a matron scrubbed his skin until he bled,” he said.

LaBelle and others spoke of the system of giving each youngster a two-digit number that was marked on their clothes and how they were called by their number rather than their given names.

“If you forgot your number, you were spanked,” he said. “Many children had difficult names to begin with, so matrons found it easier to simply refer to them by number. The children who could not speak English did not know how to follow the rules and every time they opened their mouths they spoke in their own language. They were punished by having their mouths washed out with lye soap.”

Robin Sherry, now retired with her husband Paul Sherry, also was forced as a small child to attend the Wrangell Institute. She spoke of the constant physical and mental abuse.

“They never called us by name, only by number,” she said.

Because the children were punished for speaking their Native languages, some eventually could no longer remember their Native tongue.

“Now when elders speak to me, I can understand them, but I can’t answer them,” she said. “I only went there for one year, but it took everything (culturally) away from us.”

Bob Sam, a Tlingit storyteller from Sitka, also spoke at length about his work to return home and rebury the remains of thousands of people who died at these boarding homes and psychiatric facilities, the latter being a method of declaring Native people insane to get them off land known to have gold deposits as far back as the 1880s.

“I bring people’s bodies home from institutions,” Sam told Haaland and others in Anchorage. “I have brought hundreds of bodies back from institutions to Alaska and helped to restore cemeteries.”

Over the years, dating back to the gold rush days in Nome, Fairbanks and Juneau when it took just six pioneers to declare a person insane, many Alaska Natives were declared insane to get them off of lands known to have gold and sent to psychiatric facilities in the Lower 48, he said.

Over 6,000 Alaska Natives died at one of those hospitals and the bodies of 3,800 of them are still there, “all because of the gold,” Sam said.

Speaking in a radio interview with Juneau radio station TAKU 105 in Juneau in 2018, Sam talked at length about his work of many years to bring home the remains of hundreds of Alaska Natives buried in cemeteries at boarding schools between 1878 and 1917.

He also expressed hope for the future of Tlingit culture, calling it a renaissance: “Our language is coming back. Our culture is here. Our young people are singing and drumming and dancing, and they are proud of who they are and they know where they come from. All my work is part of it because the sign of a healthy community, a sign of a healthy people is a clean cemetery.”

In his testimony Sunday at the Alaska Native Heritage Center, Sam spoke with the same passion, telling the crowd “there is so much pain that some of us don’t remember where the pain came from.”

“But we are going to heal. We are going to get past this because we are Alaska Natives. It makes us even stronger,” Sam said. “Let’s bring our language back, our culture back. It’s our right for all our children to come home.”

Learn more about the Indian school home healing program at www.boardingschoolhealing.org.